|

|

|

Arohi Ensemble

Avataar

Michael Messer's Mitra

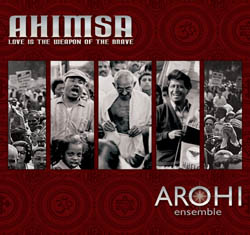

While many would cite George Harrison's study with Ravi Shankar as the genesis of Indian musical and spiritual traditions' influence on the west, well before “Norwegian Wood,” Yehudi Menuhin and John Coltrane had sounded out the Hindustani traditions of Northern India. Menuhin and Shankar (whose older brother Uday was already performing in U.S. soirees in the 1930s) met in India in 1952, and Shankar encountered Coltrane in New York in 1964. Shankar was astonished to learn that Coltrane had all his recordings, about which he asked probing questions, a confirmed vegetarian and yoga devotee immersed in the works of Shri Ramakrishna. The improvisatory character of jazz naturally entails an openness to uninhibited adaptation. The Coltrane Quartet's modal sound clearly manifested the Hindustani soundscape, as with Impressions (1963), following Coltrane's modal turn on Miles Davis's Kind of Blue (1959). South Indian Carnatic music soon figured into the jazz-fusion experiments of John McLaughlin with the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Shakti; after relocating from England to the U.S., McLaughlin became a yoga practitioner and a disciple of Sri Chinmoy. In a more secular mode, one also thinks of A Meeting by the River, the 1993 studio collaboration between Ry Cooder (slide guitar) and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (on his hybrid Indian slide creation, the Mohan veena). Improvised on the spot within an hour of the artists' first meeting, the work won a Grammy the following year as Best World Music Album. The titles reviewed here reflect these earlier tendencies. Closest to the conservatory and Indian spirituality, yet attuned to western classical strains, the Los Angeles-based Arohi Ensemble (“arohi” signifies ascending melody) is led by composer-sitarist Paul Livingstone, with Pedro Eustache (bansuri, flute), Partho Sarothy (sarod), Abhijit Banerjee (tabla), Peter Jacobson (cello, contrabass), and Dave Lewis (drums). Per the title, the project is inspired by the non-violent (ahimsa) conflict-resolution ideals of Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez. Arohi's musical guru, Hindustani singer and sarod master Pandit Rajeev Taranath, who taught at the California Institute of the Arts (1995–2005), was a disciple of Ali Akbar Khan, and also studied with Ravi Shankar.

From Toronto, led by Sundar Viswanathan (alto and soprano sax, bansuri, flute), Avataar is deep in the jazz-fusion vein. Viswanathan—who has performed with such jazz luminaries as Wynton Marsalis, Dave Holland, Vijay Iyer and Rez Abassi—is also a composer, having studied Hindustani music and the classical Turkish makam system of melodic progression. He cites influences as diverse as Shakti and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Zakhir Hussain, Trilok Gurtu, Keith Jarrett, Jan Garbarek, Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Scriabin, Alban Berg, Enya, Loreena McKennitt and so on.

Shifting into acoustic mode, down the pathway blazed by Cooder and Bhatt, English singer-slide guitarist Michael Messer's Mitra (the Hindu god of friendship and alliance) purveys a wry species of cosmopolitan Country & Eastern music. After an impromptu jam in Mumbai with Manish Pingle (Mohan veena), Messer invited him to London in 2013 to perform as a trio with Gurdain Rayatt (tabla). They reconvened in 2015 for a studio date, emerging a few days later with a natural-born blend of Mississippi Fred McDowell (“You Got to Move”; “You Gonna Be Sorry”), Muddy Waters (“Rollin' and Tumblin'”; “I Can't Be Satisfied”), J. J. Cale (“Any Way The Wind Blows,” with guest pianist Richard Causon), a traditional Indian raga, the anonymous Appalachian classic “Rollin' in My Sweet Baby's Arms,” a pair of originals, and the closing Gus Kahn-Herbert Stothart chestnut “Sweetheart Darling,” done evening-raga style. In this era of Brexit, before the empire strikes back, high time for some down-home Ganges Delta blues. - Michael Stone

© 2016 RootsWorld. No reproduction of any part of this page or its associated files is permitted without express written permission.

|

|

|

|