Balani Show Music in Mali

The most notable compilation of balani show music to date was Balani Show Super Hits (Sahel Sounds, 2014). This release introduces the listener to the frenetic flows and hectic rhythms that characterize the music in its contemporary mutation. It features the rappers from the Malian hip hop collective Supreme Talent Show, and includes two tracks produced by the well-known kora player and hip hop producer Sidike Diabate. Crucially, Sidike is a griot: descended from a long line of hereditary musicians, praise-singers and historians.

The musical tradition in Mali goes back to the great pre-colonial Mande empire, comprising modern day Guinea, Mali, Senegal and Gambia, which rose to power in the early 13th century under the great hunter-king Sunjata Keita. Music plays a central role in remembering that history, and the griots are the custodians of this oral tradition: the epic of Sunjata was passed down generation after generation, and has now been put into writing.

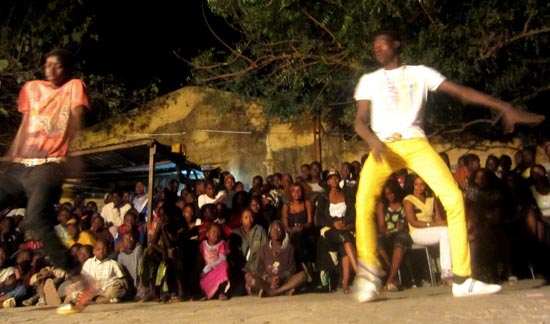

There is no more powerful symbol of Mande identity than the balafon, which is probably several thousand years old (the original balafon played by the griot of Sunjata Keita 800 years ago is still in existence). Traditionally played solely by griots in ceremonial contexts, the balafon is extremely exclusive. However other ethnicities in the region also have balafon traditions which are more democratic and serve entertainment purposes. Balani is one such tradition, emerging from the Sikasso region of southern Mali among the Senufo and Minyanka ethnic groups. Balani literally means “little bala” and is smaller than the Mande balafon, with shorter keys and a higher pitch. Providing high-intensity dance music during rural village parties, the live performance context led to its designation as balani show. Neba Solo is the artist credited with putting balani music on the map, winning Mali’s “Artist of the Year” competition in 1996 and writing the nation’s anthem for the 2002 African Cup of Nations.

In the 1990s in Bamako, balani show performances, previously a rural phenomenon, became a popular urban one. This coincided with mass urbanization as young people flooded to the city in search of opportunities, often finding themselves in precarious employment with low wages. A favorite pastime at this time was the organization of street parties, where live balani players would play the high-intensity dance music previously associated with rural life. One scandalised newspaper article claimed to have counted 100 across the city on one night, and these urban performances were often associated with thuggery, excessive consumption and violence. This was the catalyst for the latest mutation of balani show music, as in incorporated new technologies and eventually became an electronic dance music. Unable to afford live balani players, they began to use cassettes of prerecorded music. The introduction of CDs allowed producers to remix and compose their own tracks, and the cyclical balafon riffs make it a perfect fit for looping. This spawned an entirely new genre of music, which takes influences from other popular African dance musics, such as kuduro from Angola and coupé-décalé from Ivory Coast.

Balani show music holds a special position in Mali’s musical landscape and is among several underground sound cultures - such as singeli in Tanzania - adopting a DIY attitude and making use of new technologies to create high-intensity dance music, hugely popular with urban youth while being rooted in historical traditions. As these new genres of music garner attention globally, it’s an extremely exciting time for contemporary music on the continent. - Adam Rodgers Johns

Photo and videos courtesy of Sahel Sounds (www.sahelsounds.com)

|