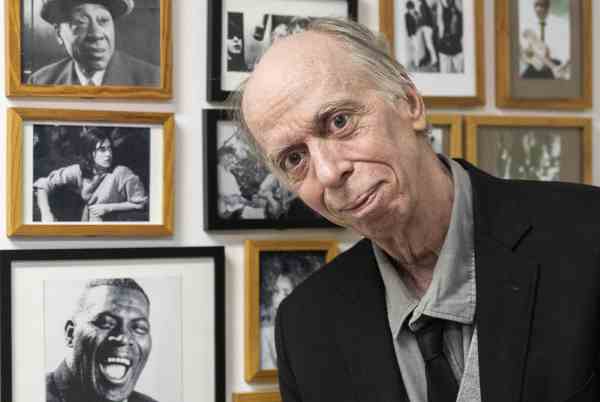

Dick Connette

Over the years, Connette has irregularly skimmed across the music-industry firmament like a comet, as a producer of others and then with his ensemble Last Forever, where he carefully designed his exquisitely wrought chamber-folk songs and assembled talented musicians to perform them. In the foreground was singer Sonya Cohen, who succumbed to cancer in 2015, seemingly bringing the project to an unexpected and lamented demise. Eventually Connette returned, calling his new project Too Sad for the Public and tapping a variety of singers for its eclectic debut, Oysters Ice Cream Lemonade in 2017. On his latest, Too Sad for the Public: Vol. 2: Yet and Still, Connette mostly turns to Canadian-born and Brooklyn-based Ana Egge as the vocal focus of the songs with lyrics. Her bluesy drawl – reminiscent of the laidback, late-night, jazz-hipster singing of Rickie Lee Jones - gives the songs a sardonic, wry sensibility. On “G. Burns in the Bottom,” which takes off from an old string-band song, Egge sings with the darkest of humor: “It’s the awful truth in a world of hurt; Nobody’s smarter than the dirt.” Though known as a musical composer, Connette also shines as a lyricist. His sung stories have the resonance of folk wisdom, but he seasons his wisdom with wry touches of absurdist wit. “I can tell time but I can’t tell it much,” says one narrator. Connette is able to evoke the struggles of his hapless townspeople while still leavening it with a deadpan sense of humor. On all his projects, Connette draws upon high and low culture, burying references to old folk, blues or rock songs, and any number of soulful traditions for the valuable raw material of his jewel-polishing operation. On Yet and Still, Connette writes his own tunes but also restrings the tunes of others.

The album opens with “Uncle Bunting (Part 1)” with Rob Moose overdubbing several string instruments for a wordless and evocative prologue to the album, a meticulous distillation of folk sounds. A couple of cuts later, for “Uncle Bunting (Part 2),” Connette conjures up a fiddle orchestra for a driving tune that simultaneously brings to mind the dusty atmosphere of a barn dance and the red velvet seats of a concert hall. “Uncle Bunting, Part 3” heads for New Orleans with a peppy tuba bass line serving as a steady foundation for the call and response of brass and wind instruments. For “Shake Sugaree,” he takes North Carolina folk singer Elizabeth Cotton’s playful lament and adds new verses, keeping the chorus “everything I got is done and pawned” as well as the song’s mixed emotional message. Where Cotton’s version is a simple guitar-based song with her pre-teen great-granddaughter singing, Connette subtly adds various textures to the tune – a minimalist slow walk on the piano’s lower register and a few blues harmonica flourishes – while Egge’s blues drawl adds ruefully funny, world-weary verses. “Learned how to drink/learned how to smoke/learned how to laugh without getting the joke.”

He channels New Orleans for two very different versions of a tune, squeezing the French Quarter bar rag for “Hey Now (Part 1),” a sophisticated but funky tangle of brass; while “Hey Now, Part 2,” strips away melody instruments, highlighting Egge’s smokey, swinging vocal as it glides atop a chattering cloud of percussion.

On another pair of songs, Connette tells the story of a “mighty bad man.” On “Railroad Bill, Part 1,” with dobro and Egge’s drawling vocals he tells the sad tale; on the contrasting “Railroad Bill, Part 2,” Connette reinvents the song with subdued tappity-tap percussion and an overdubbed 24-part harmonica orchestra. Chaim Tannenbaum takes the vocal lead here and revisits the tale of the title character. The song ends improbably with a two big electronically retextured electric guitars that are reminiscent of Brian Eno’s art-pop experimentation.

On the country fiddle tune “Train Your Child” Rayna Gellert sings a sweet, poignant and darkly humorous story of “little manish boys with their hats sitting on one strand of hair” and “little womanish girls that think themselves to be grand” cluelessly courting and getting married. The song ends with the slightly askew cautionary advice: “Before you educate their head, educate their heart.”

The album ends with another visit to “G. Burns in the Bottom” – part two here is another New Orleans-style second-line ensemble, layers of warm brass embracing and powering a swinging march. Much of folk and traditional music is rooted in the place it is from, geography being musical destiny. Connette, though, creates a nostalgia for a place that doesn’t quite exist except in the space between the lines of his songs – it’s the hardscrabble life of Appalachia, it’s the boozy joie de vivre of New Orleans, it’s the rawhide ruggedness of Texas, it’s the desolation of the Plains; yet it’s also imbued with the urban sophistication and dark quippy wit of downtown Manhattan. It’s a copious vision and embodiment of the best of America’s soul. While the U.S. is mostly thought of musically for its pop hegemony, Connette’s folk fantasy reminds us that the country is also a wellspring of simple beauty; that there’s a good heart beating out rhythms in the heartland.

Further reading and listening:

Search RootsWorld

|