The Nordic countries aren’t the first place that springs to mind when one thinks of Roma (Gypsy) music. But there are threads of Roma music and generations of musicians in the fabric of the traditional music and song in these countries as in so many others, and indeed they sometimes keep traditions alive that have almost or completely died out in the wider population.

The Nordic countries aren’t the first place that springs to mind when one thinks of Roma (Gypsy) music. But there are threads of Roma music and generations of musicians in the fabric of the traditional music and song in these countries as in so many others, and indeed they sometimes keep traditions alive that have almost or completely died out in the wider population.

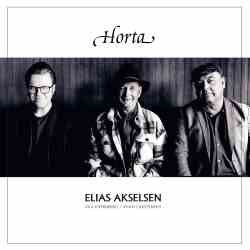

Elias Akselsen is 74, but there’s no sign of quavery age in his strong, finely modulated singing. He was born in Norway of Romany Traveller parents (in Norwegian Travellers are known as Taters; they’re said to have arrived in Norway and Sweden in the 16th century, mostly from Britain, and are not to be confused with Tartars or Tatars, who are Turkic-speaking peoples who originated in north and central Asia).

Born on the road, childhood was tough, and he spent 16 years as a street singer in Sweden, where he also performed with Cornelis Vreeswijk and other well-known Swedish musicians. Since the late 1970s he’s lived back in Norway and is the country’s leading exponent of Tater songs, upholding and disseminating his culture, making records and working with leading Norwegian musicians and receiving a number of awards and nominations.

Brilliant multi-instrumentalist Stian Carstensen has, since the turn of the millennium, been a frequent supporter and collaborator. For this new album he and Akselsen are joined by classical, traditional and jazz violinist Ola Kvernberg (brother of traditional fiddler Jorun Marie Kvernberg of the band Majorstuen), who also recorded and mixed it. Both Carstensen and Kvernberg have great command of a range of musical styles and traditions, and they draw on them to distinguish and support the variety of melodic modalities of the songs that Akselsen sings.

So the opening track, “Vandringstaven” (“Walking Stick” - giving thanks to God for the walking stick that helps the traveller through life) is very much in Norwegian traditional religious song mode, and is accompanied just by Kvernberg’s fiddle in a double-stopped dronal style that draws partly upon Norwegian fiddle tradition.

The lyrics of these songs, all of them traditional, are moving, sensitively expressed, and largely about the hardship, love and pain of being Tater.

“Burobengen” is the song of a non-Tater boy born into wealth in Setesdal, disinherited because of his love for a Tater girl, but not regretting it as many years later he sits happily with their many children. It brings in Carstensen’s accordion (the instrument from his armory that he sticks to for this album) which moves to a chugging swirl as the song picks up rhythm, with Kvernberg taking a soaring, keening manouche-style violin break.

“Fant-Sonja,” very much akin in its minor-key form to Finnish Gypsy songs, is sung by guest Anita Kleppe, a Norwegian Tater singer a generation younger than Akselsen. It’s the nuanced tale of a girl born on the land; her mother dies when she’s an infant, the man who finds and rescues her is killed in a fight. She converts to Christianity ‘and learns to believe’ and is loved by the son of the local landowner but is chased from the landowner’s house and taken in by the priest and villagers (as far as I can tell from the lyrics - I could be misunderstanding some parts), but dies and is buried with her unborn child.

“Stor-Johans Visa” (“Big John’s Song”), which Akselsen sings unaccompanied, has great melodic similarity to some English, and indeed also Irish, traditional narrative songs. It tells of Tater men who seek riches but don’t find them, who gather together to tell tales and drink coffee and (but I could be getting this wrong) alcohol made from polish.

“Det Var I Fjor Jag Tjena Dreng” (“It was last year I was a serving-boy”) is a jolly 4/4 singalong sort of thing with spirited fiddle and accordion that stylistically hint at US old-timey and Cajun as well as Norwegian gammeldans. And it’s a relatively happy song, about a boy working on the parish’s worst farm - shades of some Scottish bothy ballads - but who stays on because he likes a girl there; he pulls her out of a ditch when they both fall in, she falls in love with him, and he’s planning to marry her.

|

|

Then back to sadness in “Se Min Ild” (“See My Suffering” - a leaving-love song) in a slow waltz-time, sung by Kleppe, where the fiddle and accordion take a klezmerish approach. There’s yearning for lost love by one cheated upon in “I Månge Or” (“For Many Years”) sung by Akselsen with dronal minimal accompaniment mainly on viola, and “Två Må Man Vara” (“One Must Be Two”), which he sings unaccompanied. The booklet gives lyrics to the songs, but only in Norwegian; with help from a well-known online translator here are parts of this one:

I am a child of the forgotten race

From land to shore like a lost people

I was hated and whipped, beaten on the way

Because I was a poor child

I sit in the cell so tight, dark and gloomy

My heart wants to break, oh help me, oh God

Help me to live a life to the glory of God

And later:

But there must be two if life is to succeed

Two to build and two to live

You may be two in sorrows and joys

Two to share the daily bread.

Heart-string tugging vibrato violin and surging accordion, with klezmer-type hints of “Hearts And Flowers” and “Mayn Rue Platz,” open “Mustalainen” (the Finnish word for Gypsy/Roma), accompany a song that, given Akselsen’s own life story, seems a cri de coeur:

I wander about, always alone

I came as a stranger to mountains and valleys

I found joy in the free nature

Chains never caged me

I am poor and without a home

And so I have to reach out

The Tater boy must go alone

For his sorrows no one can understand

Down in the valley among the flower beds

There walks a girl like a bride

She bears fresh roses on her cheek

Lures flutter in the slow wind

Mustalainen, you who are my son

If you give me a shilling, hear my prayer

Born in poverty and cramped conditions

All I miss is sun and spring

To follow more of the Nordic Traveller trail, I recommend seeking out the recordings of Akselsen’s parallel among Finnish Travellers, Hilja Grönfors, who is of the same generation and is, like him, a fine singer and the leading proponent and exponent of her culture’s songs, accompanied by skilful and sympathetic non-Traveller musicians.

Further reading:

Rebelde: Forgotten Gypsy Songs of Italy

Stian Carstensen Musical Sanatorium

Henriette Flach Skyklokke

Hilja Grönfors Phurane Mirits (Andrew's review from fRoots)

|