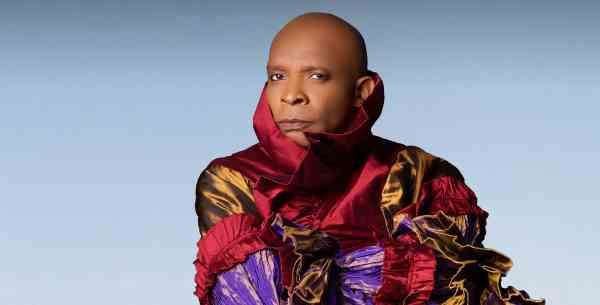

Erol Josué

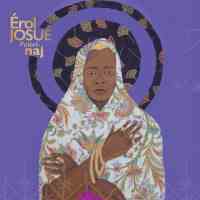

Erol Josué’s second album, Pèlerinaj (Pilgrimage), seduces listeners into a magnetic web of the spiritualism of Haitian vodou. Pèlerinaj also opens a window onto the integration of vodou and its pantheon of spirits, or lwas, into the daily life, aspirations, and politics of Haiti. In fact it was on the night of August 22, 1791, when two slaves, Dutty Boukman, a maroon of Sénégambian/Jamaican parentage, and Cécile Fattiman, of Haitian/Corsican birth, presided over the vodou ceremony that would consecrate the Haitian revolution launched on the very next day.

Erol Josué’s second album, Pèlerinaj (Pilgrimage), seduces listeners into a magnetic web of the spiritualism of Haitian vodou. Pèlerinaj also opens a window onto the integration of vodou and its pantheon of spirits, or lwas, into the daily life, aspirations, and politics of Haiti. In fact it was on the night of August 22, 1791, when two slaves, Dutty Boukman, a maroon of Sénégambian/Jamaican parentage, and Cécile Fattiman, of Haitian/Corsican birth, presided over the vodou ceremony that would consecrate the Haitian revolution launched on the very next day.

To achieve his musical and personal mission, Erol Josué has gathered together an august team of creative companions from various musical and geocultural realms, well-suited to express the authenticity and heart of Pèlerinaj’s rhythm and ritual. This dappled cohort allows the songs to reach beyond the bare-boned field recordings and unfortunate Hollywood stereotypes that have heretofore served to define Haiti’s spiritistic traditions for the uninitiated. As director of Haiti's National Bureau of Ethnology for over 10 years, author; composer; lyricist; vocalist; choreographer; statesman; vodou priest, or houngan, Josué, called by many le met (the master), campaigns for the amplification and rectification of Haitian history and culture. Pèlerinaj turns this charge into a deeply personal, heartfelt and elegant testament of his own journey, that of a pilgrim ever-seeking higher ground. Significantly, Pèlerinaj is Josué’s cri against the everlasting battering of Haiti through subjugation, slavery, occupation, internecine struggles, and natural disaster.

Kafou (or crossroads) is a powerful image in vodou. As a lwa, Kafou can be an unyielding gate-keeper at the axis of the crossing, controlling the transit of other spirits; in the song, Kafou, Josué his agency in a wrenching plea for justice for Haiti. More locally, Josué bewails the growing disrepair and neglect of Kafou, once an idyllic community on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince, where Josué spent many happy moments in his youth, but has become now unrecognizable in its squalor.

In an impressive departure, co-composer and lyricist Mike Muholland’s steel string guitar muscles seventies protest rock lines into the mix, effectively pairing the dry chill of metal with the dampened hide of percussionist Zikiki’s kongo drum. Also notable is the abrupt break coming mid-way through the song in what sounds like a brass marching band. The protest sounds and the brassy band can be interpreted and appreciated as pivotal moments in Josué’s, life informed by the many crossroads he’s had to negotiate. "Kafou" is a piquant song, its music and metaphors, compelling and complex.

Earth mother, Erzulie, is the most sensuous of the vodou goddesses. Her rhythms are bathed in luxe; she undulates before us, smooth and seductive, in the guise of keyboard, guitar and drum-beaten droplets of mercury, with bluesy hints of jazz enhancing even further her allure. Enter Josué, smitten, his voice breathless, supplicative. As his plaint intensifies, so does the agency of Jean-François Pauvros’ high wattage guitar, shattering the volupté with nerve crashing distortion. Josué does not pine for Erzulie’s romantic favors, but for her intercession to secure Haitians’ deliverance from their ineluctable fate. But Erzulie responds as if made of steel, and promises nothing. As Josué observes wryly in the album’s notes: “She plays a game of tough love.”

Throughout the Caribbean, the kwi, as it’s called in Haiti, is a catchall crucible. A hollow gourd, or calabash, the kwi holds offerings to the spirits, is used to drink or eat from, serves as a water bucket for bathing, takes on various appearances as a musical instrument. In the song, “Kwi A,” the kwi is enlisted as a beggar’s cup. Josué is dismayed that such a bold, proud people as his, with so many resources and a fierce history of resistance snd rebellion, can still need to hold out their kwi and beg for sustenance and foreigners’ aid in their continuing strife. “We are wealthy,” he despairs, “but we are begging.” The introduction to the song is abject: we hear just a mournful cello and Josué’s raw vocals in semi-recitative. This air of degradation is dispersed by a swath of added strings, summoned to resistance when joined by Bauvois Anilus’ commanding manman drum leading Nègès Fla Vodoun’s swelling vocal chorus to a crescendo with African,Western classical and liturgical passion. As Josué gives voice to countless emotions and registers on "Kwi A," he reminds us, as he does throughout the album, that he is le met of an impressively honed, pliant and stunningly emotive voice. “Kase Tonèl,” the album's finale, takes the listener to the otherworldly heights of a live outdoor vodou ceremony presided over by Josué in his calling as houngan and recorded by co-arranger and composer, Charles Czarnecki. Only the rhythmic, repetitive sounds of bare feet falling on the earthen floor can temper the anarchy of the drums. Drummer Avilus attacks his manman in a whirlwind, slamming with tough love his baget, his rough hewn, tree-carved stick, against the wooden side of his drum. Despite the music’s drift towards more party-time rhythms at its close, the fervor would no doubt be coaxing a good number of the participants back into possession. There is undeniable fury here, yes, but it is not the fury of desperation or rage, rather one that celebrates determination, culture and community. “Voila!” the celebrants exchange with one another to put the long night to bed. “Voila,” indeed. Erol Josué’s Pèlerinaj is a triumphal work of ecstasy and sophistication.

Search RootsWorld

|