|

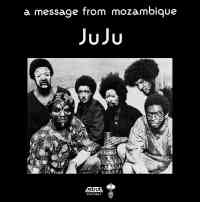

Juju A Message from Mozambique Strut Review by Bruce Miller

Saxophonist James Branch- aka Plunky Nkabinde- is a crucial part of this scene. Initially connecting with Zulu musician Ndikho Xaba in San Francisco, Plunky joined Ndikho and The Natives, another spiritual jazz group that only recorded a single LP (2022 saw this LP reissued in South Africa and the US). From there, he formed Juju, and two albums later, the more celebrated Oneness of Juju, whose records have seen a number of reissues over the last 30 years. And while the Oneness LPs from the mid to late seventies are a classic fusion of funk, disco, and jazz, sharing ground with Chicago’s short-lived The Pharaohs, the first Juju LP A Message from Mozambique, released in 1973 on Strata-East and then again on Washington DC’s Black Jazz label, is a much more raw affair.

Opening track “(Struggle) Home” crawls along a suspended chord as Nkabinde’s sax reaches for the kinds of heights Pharaoh Sanders had already perfected. In fact, his tone shares Sanders’ gruffness, as he slithers and quakes over piano and a barrage of percussion. For 15 minutes, the track rarely lets up. Three of the album’s other five tracks feature nearly everyone playing percussion, leaving any jazz-based confines behind as the group chants and locks in, while the eleven-minute “Make Your Own Revolution Now” catches the sextet in full, piano-led squall.

Juju’s shaggy ferocity valued passion over finesse, and by the mid-seventies, their brand of Africa-embracing, deeply political musical tempest had been eclipsed by slicker fusion styles, many of which have not aged well. Yet, for a few years in the late 60s and early 70s, after the father of the spiritual genre, John Coltrane, had passed, as the American war in Vietnam raged on, and as the fruits of Civil Rights helped shape popular media, radical musical gumbos such as Juju’s helped further expand what music could be in a way that showcased Black identity in a country that, 50 years later, refuses to truly listen.

Search RootsWorld

|