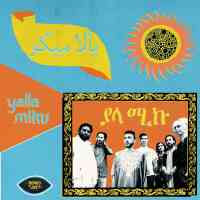

Yalla Miku

Yalla Miku, on the other hand, manages to pull from its members’ various heritages- Morocco, Eritrea, Algeria, and Switzerland to concoct a stew that reveals North and East African instruments and styles before wrapping them up in motoric hypnosis and post-punk jitters. The band, who call Geneva home, came into being when the European musicians connected with three North and East African immigrants, all three of whom have harrowing tales of hard travels and rough beginnings in their new home. Unlike the collaborators mentioned above, Yallu Miku neither dresses up the traditional in new clothes, nor largely eschews the musicians’ solo impulses. Instead, they reimagine what might be considered African or traditional in blankets of their own making, thanks to the musicians being physically connected with one another on a full time basis.

“Premier du Matin”, for example, opens with a perky synth riff that bursts into club sunshine before the drums stop, widening a platform for the vocals, which hover over synth squelches, Moroccan loutar licks, and a guitar riff as the percussion re-enters, kicking the singer into the stratosphere. Other tracks begin seemingly representative of a particular culture only to mutate midway. “Tortije” appears to be a Middle Atlas Moroccan loutar-driven meditation, but midway through the track, after a drum kit and electronics appear, it makes a shift without ever letting go of the track’s original tempo or groove. It’s a deep example of what happens when cultures collide and recognize each other’s music equally. The results feel organic.

“Hyper Tigre” relies heavily on Samuel Ades’ vocal and krar, shifting the feel across the African continent. But as with other songs here, what appears to be an Eritream folk tune with some electronic mutterings along for the ride suddenly shifts melody, language, and instrumentation radically without a hint of contrivance. Ultimately, what Yalla Miku creates shows a group of seven musicians finding as much joy in their collective powers as they have for each other’s traditions. This is less about what immigrant cultures sound like when subsumed by another identity; instead, unlike so much economic and racial politics around the world, this is the sound of people working as equals to create something at once familiar and unidentifiable.

Search RootsWorld

|