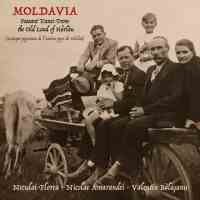

Neculai Florea, Nicolae Amarandei, Valentin Bălaşanu

But actually they are recordings made in 2019, 2022 and 2023 of the three living musicians who appear in color on the back cover, in the traditionally Moldovan region of Romania in the counties of Iaşi and Botoşani in the north-east, near the border with Moldova, playing fiddle, cobza and wooden whistles. (The sepia photos on the pack and in the booklet come from various parts of Romania and aren’t connected with the material or the people mentioned). It’s the cobza that was the motivation for Saşa-Liviu Stoianovici to record this trio. It’s a pear-shaped traditional lute with a very short neck and usually, as in this case, four pairs of strings that, close together at the neck, fan out to be more widely-spaced at the bridge to allow the pick more easily to hit a specific pair when playing melodically. Once common among the village musicians of Romania, largely in accompaniment to fiddle, both it and the number of village musicians have declined over the years. But, while most are ageing, they’ve not yet disappeared entirely; Stoianovici, himself a cobza player, in looking for remaining village cobzars and fiddlers found singer and cobzar Neculai Florea, who plays in the energetic, rhythmic style of his region. (He was born 1942, so in his 80s when most of these recordings were made, but shows undimmed vitality). Seeing the decline in the instrument and village players, Florea had decided to do something to keep it alive, pairing up with somewhat younger fiddler Nicolae Amarandei. In the recordings they’re joined by Valentin Bălaşanu on traditional wooden whistles.

It’s Bălaşanu’s whistle that leads the opening track, a fast bătuta (one of the two most prevalent dance melody forms in this collection, the other being sârba), while cobza and fiddle chug. But in the following sârba, “Sârba Lui Lascu” it duels with Amarandel’s fast but lyrical fiddle as Florea’s cobza provides a driving strum.

The majority of tracks are high-speed dance tunes, in duple or quadruple time. There is also, though, the mournful passion of the slow form of melody, doina, here represented just by the trio instrumental “Doina Ciobanului.” Sometimes, as in “Sârba Din Deleni,” which appears twice on the album, once with the trio and once solo, Florea wordlessly vocalizes the melody, a style known as ‘dârlâit’ that’s akin to several other European traditions such as Irish and Scots ‘lilting’ or ‘diddling’. Indeed he learnt some of the tunes that way, particularly from Elena Găină, a singer from Deleni, and sometimes he converts them into actual songs. (Deleni, where the recordings were made, in Florea’s house, is the commune of six villages that includes Hârlau; until 1832 the region was known as ‘The land of Hârlau’).

For one number, “Sârba Cu Năframă,” Stoianovici plays cobza so that Florea can concentrate on the mass of words that have to be squeezed into its high tempo delivery. He manages, though, to combine playing and exuberant singing in the likes of “Tâca Din Deleni,” one of three tracks featuring just his vocals and cobza. Saşa-Liviu Stoianovici’s helpful booklet notes are in English and French.

Further reading:

Search RootsWorld

|