|

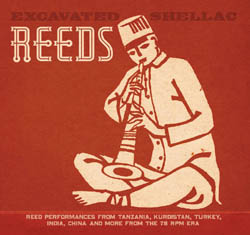

Reeds, the second volume in Dust-to-Digital's Excavated Shellac series of rare and previously unreleased recordings, is a trip back in time and across continents. The 17 tracks all feature reed instruments, those that make sound when a player's breath causes a reed to vibrate (various single- and double-reed instruments), and those that employ a wind chamber or bellows to generate sound waves (accordion, concertina, harmonium). The selections originally were released as 78 RPM recordings issued from the 1920s to the early 1950s, with one outlier, from the early 1960s. Some tracks are marred by tape hiss and other technological flaws (not surprising given that many were cut during the earliest years of the recording industry), but by and large the music comes through with clarity and presence.

Italy, France, and Spain are represented, but Reeds is anything but Eurocentric; it travels from Western Europe eastward to Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, Iran and the Caucasus, and Turkey, to North and sub-Saharan Africa and on to India, China, and Korea. It's mostly rural music made for social events and festivities, rather than commercial performance. Given that provenance, it's highly likely that these two- and three-minute tracks represent truncated versions of pieces originally played at greater length. They're stylistically varied, being rooted in particular locales and cultures. (The Italian and Chinese selections are the only ones recorded by immigrant musicians in the US rather than in their native countries.) But there are some cross-cultural commonalities. Bagpipes play on the Italian, French, and Spanish tracks, while the zurna, a Turkish double-reed oboe, turns up, in various forms, in selections from the Balkans, the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. (It made it to China in the 14th century via Central Asian Muslims.) The zurna has a range of only an octave and a half, but it's nonetheless a powerfully expressive instrument, with a sharp, biting sound that carries over any accompaniment.

Another commonality among the otherwise disparate tracks is their intense, passionate quality; the breath-activated "aerophones" (the technical term for wind instruments) cry, keen, and shriek, while the free-reeds (accordion, concertina, and harmonium) generate excitement through repetition of melodic-rhythmic motifs.

There's something else a number of the selections have in common: they were recorded in countries under foreign rule — Egypt under the Ottomans; India, South Africa, and Tanzania by the British — and by ethnic minorities — Azerbaijans and Kurds in Iran.

The CD notes identify most of the musicians and where and when the recordings were made. But for some, even that basic information is lacking. I Tre Antonio della Basilicata (Three Anthonys from Basilicata) recorded "Tarantella Popolare" at the Victor Studios in New York in 1927, but that's all we know about the trio, a zampogna (southern Italian bagpipes) player accompanied by the two other Tonys on the double-reed ciaramella. "Ekâri Eseelimmit" by Selim Leskoviku, was recorded around 1929 "in Tirana or Istanbul." Some tracks have fascinating backstories. Ahn Ki-Ok, the zither player who accompanies the little-known reed player, Kin Yin Kuan, on "Janggochum," was "a hardline communist" who in 1945 relocated to North Korea and became the dean of the musicology department at Kim-il-Sung University. Parush Parushev, a street-singer from "the Thracian city of Plovdiv," shows off amazing chops on the harmonium, which, on "Ruchenitsa," he plays like a Bulgarian bagpipe. The unidentified accordionist on the Tufanpur Orchestra's "Reng-e Ghafghaz" also is a marvel; he makes the up-tempo Azerbaijan dance number one of Reeds' greatest finds.

A couple of tracks sound like proto-free jazz. On "Raga Alapana," recorded in India sometime in the 1930s, T. Rajarathnam blows like an avant-gardist, unleashing wild, extended runs on the two-octave nadaswaram, a wooden, double-reed oboe. The uncredited zurla player on "Macedonsko Oro," accompanied only by a tapan drum, comes on like a Macedonian Ornette Coleman, with a raw, piercing tone and vocalized sound.

If those two numbers sound like forbears of a certain type of Western avant-gardism, "Into Ezimnandi" reveals the roots of a 1980s American pop megahit – Paul Simon's South African-inspired album, Graceland. Cut in the mid-1950s by Mqonga Sikanise, a solo concertina player, the piece is in the "gumboot" dance style Simon adapted for "The Boy in the Bubble" and "Gumboots." Did Simon ever hear Sikanese? Who knows. But he may have – some of Sikanese's recordings are available as 78s on the Gallotone label. (The British ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey made field recordings of Sikanese, which were released commercially by Gallotone in the '50s.) At any rate, kudos to the (wonderfully named) Dust-to-Digital for "excavating" this, and the other shellac recordings rescued from obscurity and compiled for Reeds.

George de Stefano

|