Various artists

Lu Edmonds, a member of Public Image Ltd and at various times of 3 Mustaphas 3, The Mekons, Billy Bragg’s Blokes, Les Triaboliques and many more bands stretching back to and through punk times, didn’t so much get lost in Tajikistan as sucked in. At first, in 2004, it was as an interpreter for a biodiversity project. (He speaks Russian which, while Tajiks generally speak Tajik, is used as an inter-ethnic means of communication). But he got more involved, meeting and helping musicians create performances (which have now grown to include the annual Roof Of The World festival in the high Pamirs), get their instruments repaired with the help of London luthier Andrew Scrimshaw, and also surreptitiously digitising a mass of recordings of musical material from the old Soviet archives in the country’s capital of Dushanbe.

The first five tracks are by the group Mizrob, featuring Iqbal Zavkibekov on setor (Tajik long-necked steel-strung lute) and guitar, singer Davlat Nasri, who also plays harmonium and dotar (another long-necked lute), and percussionist Zarif Pulodov. In melodic form and sound it could broadly be described as having a middle-eastern feel, with a modal melody over drone and rippling darabukka or tabla-type percussion, but while a root drone is implied there are also harmonising lines. The first two tracks are instrumental; in the third enter Nasri’s vocals, perhaps comparable to some of the melismatic declamatory singing of the Indian sub-continent, while “Hurshedam,” with its winding harmonium melody line under Nasri’s singing, is in a flamenco-like mode. (I’m making these observations as description, not analysis).

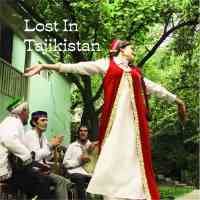

The group Samandar gets the next three tracks. Led on vocal, guitar, bass, and lab chang (Tajik jew’s-harp) by Samandar Pulodov (picured above), who is also composer of the songs (one with traditional lyrics), it also includes Iqbal Zavkibekov and Zarif Pulodov. Echoing Jew’s-harp and a repeating picked guitar line begin this ensemble’s progressive approach to the tradition. After the hypnotic “Ay Gulak,” “Dam Hama Dam (Ali Ali),” has a big, surging sound comprising lead and group vocals over the insistent pounding beat of bass and the clicking of tabla-like hand percussion; it’s strong, commercial-sounding (in a good way) and almost bhangra-like. “Dili Dilidor,” is similarly big and powerful; its chanted vocal has hints of rap, there’s the shivering twang of lab chang, massed percussion, and the wild wailing of an electrified fretted instrument.

The two tracks by the five-member Samo are in more old-tradition vein. In the strongly rhythmic “Mastynoz” the group vocals are joined by ghijak (spike fiddle), rubob (lute with a skin soundboard), tanbur (metal-strung long-necked lute) and shuffling daf percussion. “Yod Bod” begins with improvising modal phrases in free rhythm on gutty picked and strummed rubob and tanbur, before moving on to a steady slow pulse.

The three tracks from setor virtuoso Davlat Nazar were recorded in his home in the small city of Khorog, a thirteen-hour drive up from Dushanbe through the mountains along the M41 Pamir highway. He’s accompanied by an ensemble whose members aren’t specified, but sound like they’re perhaps some of those previously mentioned. “Ali Sheri Khudo” also features a fine but un-named female singer. Then it’s upward along rough tracks by 4x4 to the villages, for a welcoming song to Mihonyar village from Sultan Nazar self-accompanied on rubob, with answering voices.

The album ends with Shanbe of Barsem village singing, just to his periodic drum accompaniment and supporting vocals, a song which, according to Edmonds’s liner notes, is “all about life, the universe, everything.” At over 16 minutes, though, while obviously an important representation of the songs of the high mountain villages and the traditions that survive there, it’s a tough and long listen, at least for those of us without the language to understand. It’s taken nearly two decades for these recordings to make it to release, thanks not only to the boldly-going Lu Edmonds and those who helped him, but also to Leo Abrahams for “doggedly insisting a CD was lurking in there.” He was right; it’s well worth hearing not just for a glimpse of Tajikistan’s roots musical traditions but also for the impressive new music Dushanbe-based musicians are developing from them.

Further reading:

Search RootsWorld

|

The recordings on this album aren’t from archives, though. They’re from 2008 when, with the help of Taneli Bruun of Helsinki’s Global Music Centre, Edmonds and key Dushanbe musician Iqbal Zavkibekov, put together a 16-track recording setup in Dushanbe’s Gurminj Museum of Musical Instruments, founded by Zavkibekov’s musician and film-star father Gurminj. We’re not talking Abbey Road here. It was -20°C outside, and although the museum was heated, much of the warmth came from the musicians who packed in to grasp an opportunity to record. It’s only now that those recordings have been cherry-picked and mixed (in London by Leo Abrahams) to make the album.

The recordings on this album aren’t from archives, though. They’re from 2008 when, with the help of Taneli Bruun of Helsinki’s Global Music Centre, Edmonds and key Dushanbe musician Iqbal Zavkibekov, put together a 16-track recording setup in Dushanbe’s Gurminj Museum of Musical Instruments, founded by Zavkibekov’s musician and film-star father Gurminj. We’re not talking Abbey Road here. It was -20°C outside, and although the museum was heated, much of the warmth came from the musicians who packed in to grasp an opportunity to record. It’s only now that those recordings have been cherry-picked and mixed (in London by Leo Abrahams) to make the album.