"Took old Geronimo by storm,

And they ripped all the feathers off his uniform!"

Warden, warden, can't you see?

Be kind and set Geronimo free!"

So goes "Geronimo's Cadillac," a Michael Martin Murphey song

recorded by Dick Gaughan and dedicated in performance to Native

American hero and prisoner, Leonard Peltier. Gaughan sees a direct

link between the injustice of Peltier's captivity and the suppression

of the will and the hopes of downtrodden peoples worldwide. He says

that the history of meddling by brutal outsiders is a subject

well-known to Scots.

So goes "Geronimo's Cadillac," a Michael Martin Murphey song

recorded by Dick Gaughan and dedicated in performance to Native

American hero and prisoner, Leonard Peltier. Gaughan sees a direct

link between the injustice of Peltier's captivity and the suppression

of the will and the hopes of downtrodden peoples worldwide. He says

that the history of meddling by brutal outsiders is a subject

well-known to Scots.

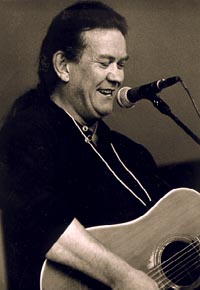

"We used to elect our king in Scotland, you know. The last one we elected was MacBeth," quips Dick Gaughan, working hard to adjust his acoustic guitar to "bagpipe tuning" just prior to a sold-out show in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Gaughan goes on to criticize the inherited-monarchy system of the UK, class injustice and unrepresentative government in general. "I think Mrs. Windsor [Queen Elizabeth] is probably a very nice, wealthy woman, but there's few Scots want her telling us what to do in our own country," he chuckles. He asserts his own belief in Scottish Republicanism, and undiminished hope for democratic rule to triumph worldwide.

Sprung from Highland Scots and Irish parents, Dick Gaughan is the established Bard of Edinburgh, a central figure in the 1970s Celtic folk revival with The Boys of the Lough, and one of the world's most admired guitarists and songwriters. His early solo record, Handful of Dust, is an essential classic. His work with Billy Bragg, Andy Irvine and the bands Five Hand Reel and Clan Alba is legendary.

Asked about the Scottish tradition of sad songs longing for the return of "Bonnie Prince Charlie" and a lost golden age of the Highland Clans, Gaughan snorts in disgust. "Charles Edward Stuart was a bloody cretin! The man spent hardly two years of his whole life in Scotland and he was a terrible coward! Most of those damned songs were written a hundred years later by people who never knew him or what suffering he caused the Scots!"

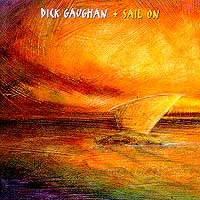

Indeed, on his latest CD, Sail On, Gaughan "slags off" both Bonnie Charlie, ("He ran like a rabbitt through the glen/Leaving better folk than him to be butchered") and weepy-eyed Scots nostalgia addicts, ("Waiting for the Jacobites to come and save the land"). Dick's Gaughan instead turns a clear eye on history and on present-day human struggles, as he calls for a true "rising" of the poor and disenfranchised in songs like "No Cause For Alarm":

"They're trying to say our time has passed,

Hell, it hasn't even started!

They haven't stopped us, and they never will!

Gonna run to the top of the nearest hill,

And dance 'til the sun comes up!"

In part a response to the fall of the Soviet Union, this song is

a hard-rocker in which Gaughan uses his Stratocaster and his strong

voice to challenge cynics directly and to assert his renewed faith in Socialism

and in "Love . . . a beacon shining in the darkest hour"

In part a response to the fall of the Soviet Union, this song is

a hard-rocker in which Gaughan uses his Stratocaster and his strong

voice to challenge cynics directly and to assert his renewed faith in Socialism

and in "Love . . . a beacon shining in the darkest hour"

Dick Gaughan is a politically-committed man. He cites his ties to the Scottish working class and their hardbitten years of struggle under Tory rule that forged his committment through strikes and turmoil. He recalls how the murder of Chilean folk singer Victor Jara by the fascist Pinochet regime galvanized Gaughan into putting his music where his heart already was. "I knew then I couldn't just play old tunes. You had to speak out. And, really, that is what the tradition is about. Traditional music--which to me has always meant just the songs that people sing and listen to, be that rock 'n' roll or old ballads--it has always had to do with politics. People's music, folk music if you will, is very dangerous stuff! It is subversive to acknowledge that ordinary people actually have a culture with artistic merit. This gives the lie to those who would like us to think that the poor are poor because they are stupid! There is a lot of wisdom in some of those old songs, and no reason I can see why songs about the politics of today are not part of The Tradition! I sing 'em, anyway, and that's the tradition I know."

Gaughan's in-your-face progressive politics, and the effectiveness of his delivery, doubtless were a factor in the visa problems he experienced over the years when trying to get into the US to perform. (One Gaughan song asks, "What the hell would Abraham Lincoln say/If he could see America now?") But when asked how he feels to be touring the US now, he tells this reporter that he thoroughly enjoys "meeting the people" here. "People, just lots and lots of new people to meet, and we have such grand conversations, both on and off stage! Governments have nothing to do with it, and the worst government can't do a damned thing to stop people getting toghether! It's grand! Besides that, I am addicted to country music, and your radio is full of it!"

Certainly, a Gaughan concert does not feel like a sombre lecture, though very weighty issues and ideas are touched upon. His Celtic black humor cuts through the performer-audience barrier, and very soon it seems he is performing in a living room, among a crowd of close friends. "I never have a set-list," says Gaughan, "I just know the first song for the evening, and we go from there depending on how the audience steers me. I love that!"

|

"Well, it's high time we swept the future clear, For those lies of the past are all they've ever been!"

"No Gods and Precious Few Heroes" |

Calling Mel Gibson's movie, "Braveheart," "at least 5% accurate," he proceeds to shake his head at the things many Americans think constitute "Scottishness": plaid and haggis and British marching bands among them. "We laugh a lot about all that Rob Roy crap," he says, inviting the audience to come over and visit "the real Scotland." "You might get quite a surprise, y'know, but we'll make you all welcome," he grins.

Then, his guitar at last tuned to an approximation of the keening sound of the pipes, Gaughan introduces his masterpiece, a meditative rendition of Hamish Henderson's "51st Highland Division's Farewell to Sicily," (recorded on SAIL ON and reproduced, amazingly, in concert). Having explained that this song was written by a Scots intelligence officer in World War II as a way to bid farewell to his comrades about to embark for the D-Day invasion, Gaughan notes that it has "haunted me for years." The mystery of his performance and the eerie journey on which he takes his listeners shows what he means by "haunted." Truly a tune of death, life and much beyond.

"I can't stand what the racists here have done with their perversion of things 'Scottish', Gaughan tells this reporter, referring to the KuKluxKlan misuse of burning crosses and other symbols vaguely linked to the Highland past. In contrast, Gaughan muses on the "reality of what life is for the people here, particularly the people of the land like the Pueblos and other American natives. You know, when the Indians first met Scots, they called us 'white Indians'. And they were right. We really are a lot like them. I might believe in many things which you or someone else might think very very strange. But, hell, that's my own business, isn't it?"

Gaughan goes on to explain that he often describes himself as "an atheist" in order to cut short prying inquiries into very personal, even mystical, beliefs. He surely has little time for orthodox religion ("Stand Up for Judas!" is one of his favorite songs by fellow songwriter Leon Rosselson.). But in another song from SAIL ON, he speaks admiringly of religious folk who act on their beliefs in solidarity with the oppressed. Always wary of icons and symbols that can be misused, Gaughan clearly places his values in human contact and the worth of hard work and united struggle for justice. "I tend to side with people like the Diggers, those English revolutionaries who fought without weapons for a fair share of the land that rightfully was the property of everyone to begin with," says Gaughan, summing up his philosophy, and smiling.

"Ye rich take warning, Ye poor take care,

This earth was made a common treasury for everyone to share!

Ye Diggers all stand up for Glory, stand up now!"

("World Turned Upside Down," - Leon Rosselson)

Dick's most recent recordings are Sail On and Redwood Cathedral, available on Greentrax (Europe) and Appleseed (US)

Article by William Nevins, summer, 1998

Photo: Genia Ainsworth, courtesy Appleseed Records