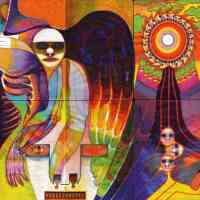

Chouk Bwa & The Ångströmers

Somanti certainly feels as if they never stopped, though its power might be a reaction to the fact that a public health emergency forced them to do that very thing. The basic concept- relentless hand drumming and call-and-response vocals filtered through an often subtle haze of electronics hasn’t changed. Yet the new album feels busier, more urgent, louder. At times, it’s unclear just what role the Ångströmers play in any of this; elsewhere squelches and blips sneak in and out of the stew Chouk Bwa create. It’s a bit like trying to spot Brian Eno’s contributions to those first two Roxy Music albums. The fact that this record was done in a single day after their tour last year might have something to do with the energy here.

“Kimelem” is as good an example of any into what this pairing is capable of. Leader Jean-Claude 'Sambaton' Dorvil’s guttural shouts demand reactions form the chorus of vocals; the drumming gives dubby echoes and slithering analogue synths a foundation to create stealth and menace as the track approaches cave-like sustain. “Sala” begins with a call over a synth drone, as if the singer is conjuring the help of a god, before the rest of the band slams forward with a drum-based upper cut that never relents. It’s at once celebratory and deeply intense. They perform as if their lives depend on the moment.

Yet, “Kote Map Mete Iwa Yo,” this time led by the female vocalists in the group, forgoes the percussion altogether, forging insistent declamations that would be a Capella save for the electronic underpinnings. It feels like- and likely is- a request for vodou spirits to join them in a moment of calm in the torrent of drums that are otherwise such a crucial aspect of Chouk Bwa’s sound. With or without the collaboration with the Europeans, nothing about this music sounds either old or contrived. Yet, the Ångströmers’ manipulations are as inventive as they are respectful of the thick, ever-knotted and moving roots anchoring Chouk Bwa’s music. As the laughter at the end of the LP’s final track, “Viyaya Keke” suggests, Haitian vodou and its ongoing practice are a boundless force of resistance and rebirth.

Further reading:

Search RootsWorld

|

Between 2020’s Vodou Alé and Somanti, this collective of Vodou-steeped musicians from Gonaives, Haiti and Brussells-based electronics duo The Ångströmers faced pandemic-based separation, but also managed to release a few EPs as well as a European tour in 2022.

Between 2020’s Vodou Alé and Somanti, this collective of Vodou-steeped musicians from Gonaives, Haiti and Brussells-based electronics duo The Ångströmers faced pandemic-based separation, but also managed to release a few EPs as well as a European tour in 2022.